J.T. Ginn and the Era of the Controllable Starting Pitcher

The timespan starting in mid-July and up until current day could most aptly be described as “The Era of the Controllable Starting Pitcher”. Trade deadline chatter was dominated by the likes of Joe Ryan, MacKenzie Gore, and Edward Cabrera, among others. The corresponding discourse involved not only their respective skillsets, but also their requisite lofty acquisition cost. A cost so lofty that none of the aforementioned starters ever seemed close to being traded.

Fast forward to December 2025’s conclusion and the story seems much the same aside from a few caveats. Somewhat outsized cost holds firm in today’s marketplace, but every noteworthy starting pitcher transaction shifts internal models’ understanding of how the market values starting pitchers. The two best examples being Dylan Cease’s 7 year $210 million mega deal and the recent Shane Baz blockbuster which saw significant prospect capital change hands for a pitcher on an upward trend with his prime controllable years forthcoming.

What bugs me the most about this discourse is how fans view offseasons (and players) as binary - the ideology that “if x team doesn’t get y player then their offseason can be graded as z”. This kind of thinking holds two principles as dogma.

This ideology’s first axiom is that transaction quality depends on the transactions of your opponents/rivals. Yankee fans, for example, feel an intense amount of pressure to match the rival Blue Jays’ Cease signing with either a signing of a front-line starter like Tatsuya Imai, Framber Valdez, or Ranger Suarez. If not those three, a trade for Joe Ryan may suffice. This kind of assumption is particularly dangerous because (presumably most) front offices are operating in a sort of surplus value meta where they’re not trying to overpay just for the sake of “keeping up with the Joneses”. This creates a disconnect between the fanbase’s desires and the front office’s overarching goal: to net surplus value through each player acquisition irrespective of opponents’ transactions.

The second core tenet of this belief set is that player value is universally agreed upon. The media, interested teams, and the Twins all likely have different understandings of Joe Ryan’s true talent. As much as public models are sold as completely objective, the reality is that choosing features for a model to determine player value is somewhat of a subjective process. Every organization has slightly different valuations on players because their models favor different statistics that they have found to be predictive. So to say that a team had a poor offseason because they didn’t acquire y player discounts the reality that the team very likely doesn’t hold the same belief about y player’s value for myriad reasons.

This ideology pushes certain flashy names to the forefront of trade discourse, like Cabrera, Ryan, and Gore, who are elevated by media narratives not merely because of rumors, but more so because of their flashy, stuff-heavy pitching profiles. I think this leaves certain controllable arms underdiscussed in the public forum, chief among them Athletics right-hander J.T. Ginn.

I’m going to break down why I believe Ginn is one of baseball’s most underappreciated and potentially undervalued arms by breaking this analysis into two parts: who he is and how he could improve. Who he is will cover what we currently know about Ginn. I’ll highlight his mechanics, his arsenal, and the batted ball outcomes that his arsenal generates. How he could improve will address how Ginn can quell batted ball outcome shortcomings through pitch design.

Who J.T. Ginn is

I got into J.T. Ginn early last season when THE BAT listed Ginn as a top 100 pitcher with relatively little MLB success. That led me to tracking Ginn throughout 2025 and last season only saw him rise THE BAT’s rankings. Ginn currently sits as the 57th best pitcher in MLB by context-neutral projected “true talent” ERA, surrounded by the likes of Pablo Lopez, Trevor Rogers, Nick Lodolo, Michael King, and Jack Flaherty, a group of starting pitchers who the public would, without hesitation, widely agree are in a different echelon than Ginn. This leads to the question: why does THE BAT rank Ginn so highly?

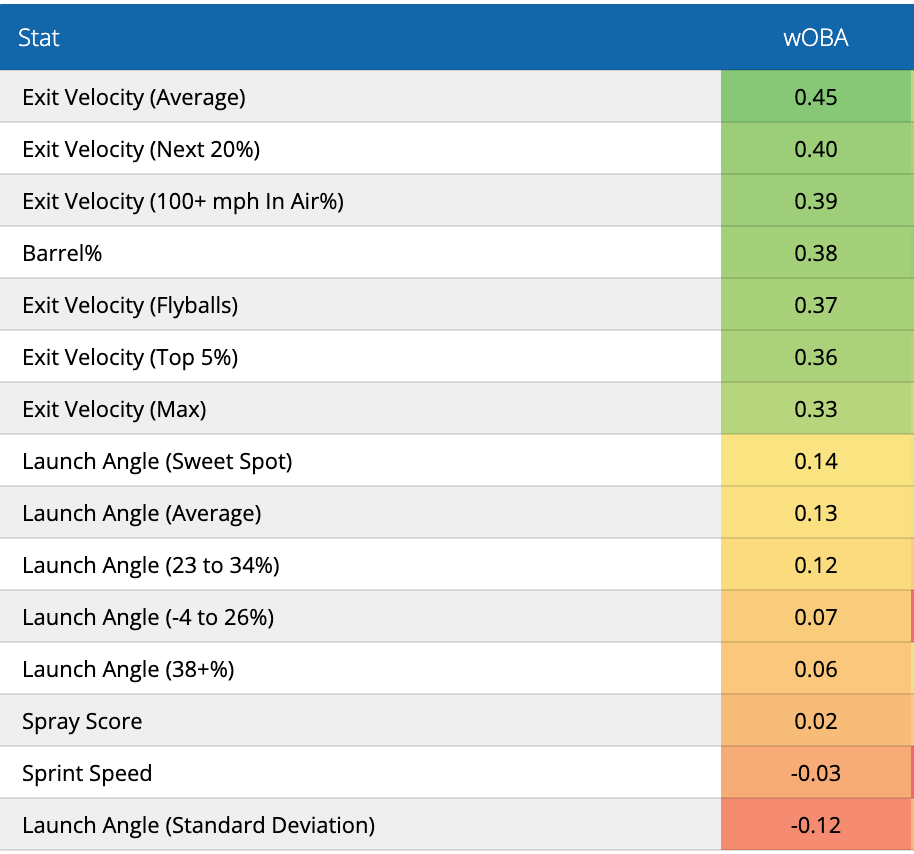

As previously described, projection models are dependent on the features they choose to estimate true talent. Luckily, THE BAT publishes a correlation matrix of what features the model deems most predictive of player talent:

Several statistics with correlations to wOBA exceeding .3 are readily visible in the increasingly pervasive Baseball Savant circles analysis:

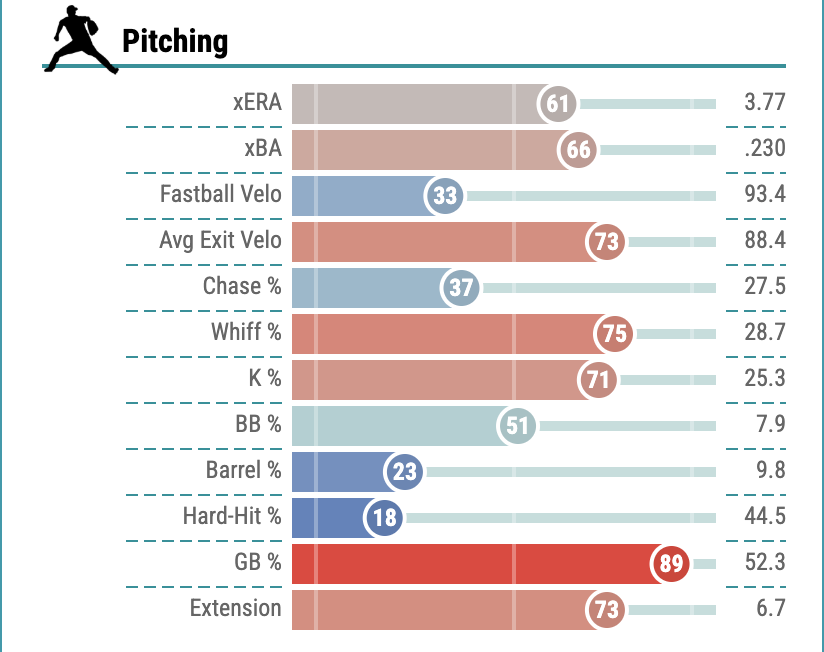

A 73rd-percentile average exit velocity and 23rd-percentile barrel rate don’t exactly inspire confidence in THE BAT’s view of Ginn as a back-end SP2 or front-line SP3. EVAnalytics, the site that houses THE BAT’s inner workings, doesn’t post exit velocity (next 20%) or exit velocity (100 mph+ in air%) so we’re going to need to recreate leaderboards for these using Statcast data. To properly build these stats using batted ball data we need to keep in mind the working definitions of each stat:

Exit Velocity (Next 20%) - “The average exit velocity of the top 5% through 25% of the hardest balls the player hit”

Exit Velocity (100 mph+ In Air%) - “The percentage of balls hit into the air by a batter that have an exit velocity of 100 mph or greater”

Exit Velocity (Flyballs) - “The average exit velocity on balls labeled by MLBAM as a flyball”

The code for these stats can be found here. Ginn’s percentiles (among pitchers with >= 100 BBE) for the aforementioned stats are as follows:

Exit Velocity (Next 20%): 9th

Exit Velocity (100 mph+ In Air%): 5th

Exit Velocity (Flyballs): 38th

When opposing batters elevate the ball, Ginn gives up low expected value outcomes. Ginn’s worrisome 19.9% pull air% further evidences how when Ginn gives up hard contact, it’s usually flyballs to the pull-side. The good news for Ginn is that his 52.3% ground ball rate ranks in the 89th percentile. Here are Ginn’s percentiles for the above three exit velocity categories, but only including ground balls:

Exit Velocity (Next 20%): 46th

Exit Velocity (100 mph+ On Ground%): 52nd

Exit Velocity (Groundballs): 62nd

Again, these numbers aren’t convincing towards the thesis of Ginn being a top 60 pitcher in the sport. So what does Ginn have going for him? We know at a baseline that pulled flyballs are poor outcomes and that we want to (generally speaking) prioritize pitchers who generate ground balls and strike batters out. There are only 5 pitchers in all of baseball (BF > 300) who have a strikeout rate north of 24% and ground ball rate exceeding 50%: Logan Webb, Yoshinobu Yamamoto, Nathan Eovaldi, Cristopher Sanchez, and J.T. Ginn. The answer to why J.T. Ginn ranks so highly may be as simple as falling at a hard-to-reach crossroad of elevated K% and GB%.

On name value alone it seems a bit shocking that Ginn falls in this class of starter. Last year, that group of starters posted fWARs of 5.5, 5, 3.7, and 6.4 with Ginn sporting a comparatively paltry 0.8, begging the question of why Ginn’s results fall so far from the rest of the group.

What stands out most amongst the Webb, Yamamoto, Eovaldi, Sanchez group is their ability to require hitters to answer several different questions. Webb relies on an east-west game, forcing hitters to not only figure out which direction he’s going, but also deciphering a changeup and fastball that play directly off his dominant sinker. Both Yamamoto and Eovaldi are pitchers who take advantage of the laws of pitch decay by throwing five pitches in flat distributions against both sides. Sanchez throws both a plus-plus sinker and plus-plus changeup with similar movement and differing velocity, a combination that baffles hitters and demands precise pitch recognition.

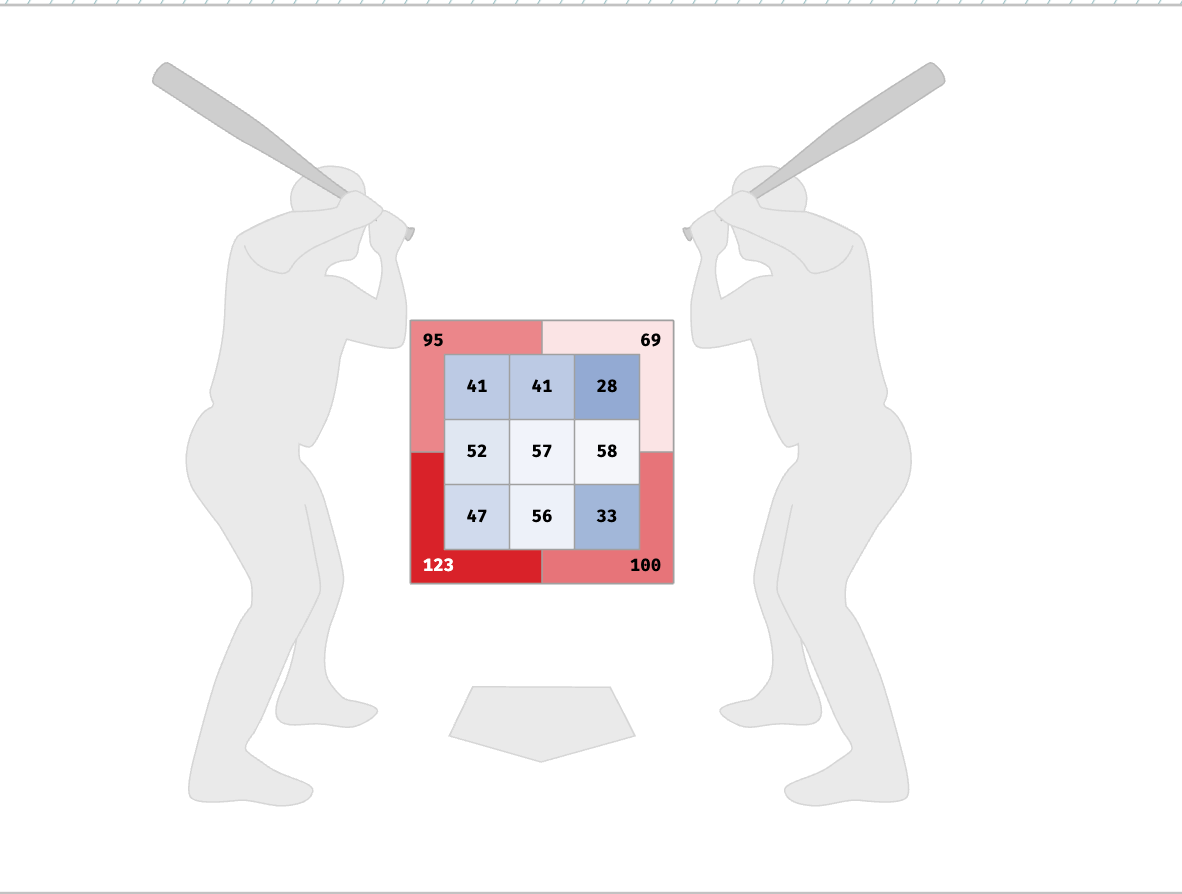

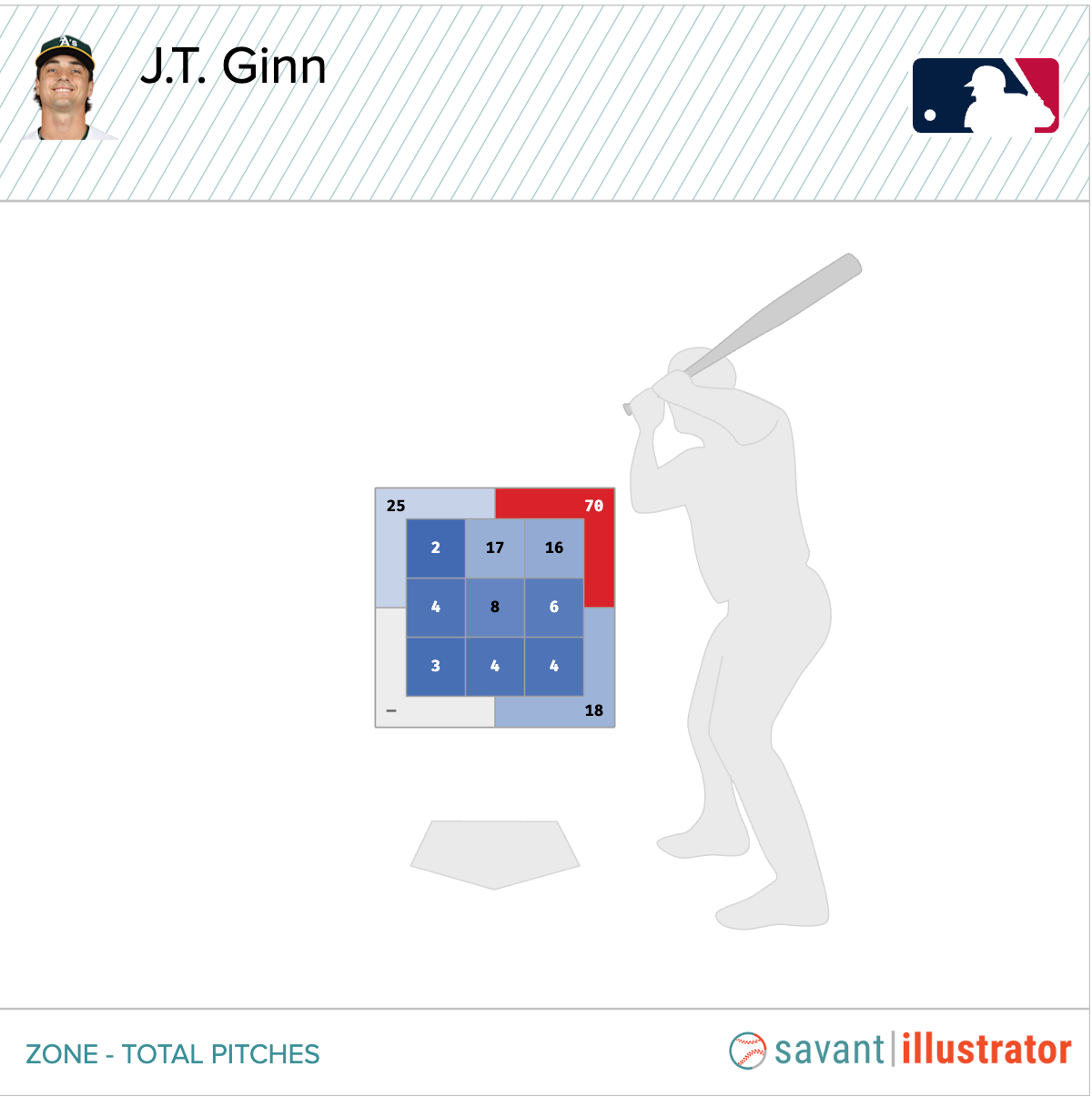

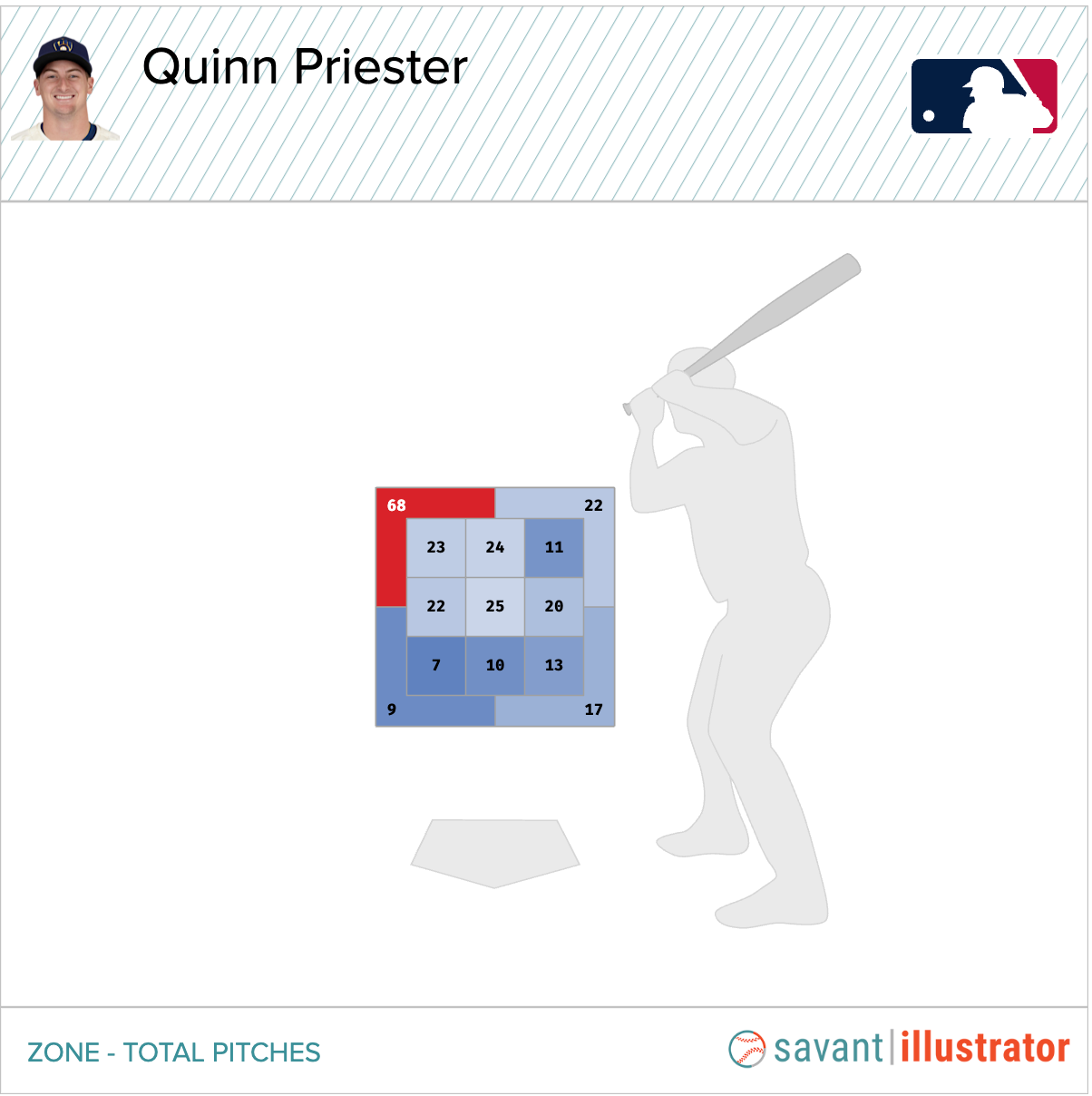

We know that Ginn generates plenty of ground balls and an above-average amount of strikeouts, but the primary concern is curtailing barrels. The etiology of this issue lies in poor secondaries and a pitch mix that exacerbates the problem. Ginn’s anchor, a 109 stuff+ sinker with a 108 location+ in 2025, serves as the foundation that the rest of his mix must play off. Among pitchers with 90+ IP, that sinker’s 123 pitching+ would’ve ranked eighth in the league, alongside Bryan Woo, Paul Skenes, and Tarik Skubal. Ginn uses his sinker at clips north of 40% against both sides with a fairly uniform in-zone pitch distribution and has a preference to throw it out of zone.

2025 J.T. Ginn sinker location against both right-handed and left-handed hitters

This preference manifests itself with a 49.5% shadow%, good for four percentage points above league average on sinkers. What especially stands out is a 23.4% putaway% on his sinker, ranking second in all of baseball (min. 600 sinkers thrown) behind only back-to-back Cy Young winner Tarik Skubal. Ginn’s sinker also posts above-league-average marks in xwOBAcon (.317) and barrel% (6.4%). In short, Ginn’s path to success hinges almost entirely upon his sinker’s strength and any effort to improve his overall profile must remain cognizant of its importance.

Ginn’s approach to retiring hitters meaningfully varies by handedness. Against left-handed-hitters, he prioritizes cutters up and in, sliders down and in, changeups away, and sinkers throughout the zone. Right-handed-hitters see sliders down and away and sinkers throughout the zone as well, though predominantly down and in. Part of the reason Ginn is willing to deploy his sinker broadly (against both sides) is his general strike-throwing struggle. Below is Ginn’s zone% compared to the league average for each pitch type:

Pitch type: Ginn’s zone% | zone% league average (deviation from league average)

Sinker: 52% | 58% (-6%)

Slider: 40% | 46.8% (-6.8%)

Cutter: 39% | 53.8% (-14.8%)

Changeup: 27.7% | 39.2% (-11.5%)

This trend proves especially worrisome because Ginn’s slider, cutter, and changeup grade out as objectively poor offerings in a vacuum. His gyro slider features a shape that stuff models tend to penalize (84 stuff+), though Ginn has shown a propensity to locate it, posting location+ clips at 115 and 119 over the past two seasons. The cutter has an extremely weak 75 stuff+, while the changeup carries a similarly awful 87 mark. Without the ability to consistently throw these pitches for strikes, they become largely ineffective outside of tunneling effects, which offers limited conviction regarding their efficacy.

The above video illustrates the tunnel between Ginn’s sinker and changeup. While the pitches initially mirror one another, the slower changeup features a noticeably loopy shape that undermines Ginn’s primary strength: a late-breaking sinker. Because Ginn exclusively throws his changeup down and away to lefties, the pitch has relatively little utility because hitters can easily sit down and away, attempting to lift the ball because of its shape. Every hitter facing Ginn understands that the sinker is the pitch they must defend against, as his goal is to induce ground balls. They know that Ginn’s goal is for them to hit the sinker on the ground. To counter that, most notably in down and away locations, hitters manipulate their bat path in an effort to elevate. The results speak for themselves: Ginn allowed a 15% barrel rate on changeups to lefties, paired with an egregious 50% hard hit rate. His .341 xwOBAcon on the pitch was 45 points worse than league average.

Ginn’s cutter is similar to his changeup in that he deploys it almost exclusively to left-handed-hitters and primarily in the same location - up and in. I actually like the tunnel Ginn creates here. While the video shows the pitch against a righty, the cutter’s gyro tendencies and natural pairing with a late-breaking sinker are evident.

The slider tells a similar story to the cutter. In a vacuum does the pitch grade out well? No. Does that mean it is objectively a net negative in his arsenal? Also no. Once again, the gyro shape appears to be a natural pairing with his sinker. The two pitches share a tunnel for the majority of their flight, preventing hitters from simply sitting on the sinker. Ginn throws an overwhelming number of sinkers down and away to right-handed-hitters, a natural solution for an arsenal built around a sinker attempting to jam same-handed batters. The slider’s 5.9% pull air% (9% league average on sliders) suggests that it functions as intended in Ginn’s approach to righties. Sliders to left-handed-hitters, however, paint a very different picture - one dominated by hues of pulled flyballs, accented by barrels to all fields, and set against a background nearly devoid of ground balls. Van Gogh would likely be as repulsed by this painting’s unsightliness as any pitching coach across MLB.

How He Can Improve

What emerges from the analysis above is that Ginn’s primary limitation stems from a lack of viable secondary offerings. His sinker carries sufficient weight on its own, but where Ginn falls short of Yamamoto, Webb, Eovaldi, and Sanchez is the presence of elite secondaries – Yamamoto and Eovaldi with their splitters, Webb with his sweeper, Sanchez with his changeup. For J.T. Ginn, that complementary weapon is absent. Before exploring what he could or should add, it’s first worth addressing how he can amend his current pitch mix to correct his most pressing flaw: a high barrel rate.

A natural comp for Ginn’s current movement profile is Quinn Priester of the Milwaukee Brewers– a sinker-dominant, three-quarters-to-high slot right-hander who complements his sinker with a gyro slider and cutter. Priester possesses elements that Ginn lacks, just as Ginn has traits Priester needs. Priester’s 7.3% barrel rate would elevate Ginn from a SP3 to a legitimate frontline starter, while Ginn’s 25.3% strikeout rate would allow Priester to make a similar leap. Fortunately for Ginn, elite sinker traits are not easily acquirable, whereas the barrel rates that plague his profile are malleable via refined pitch locations and addition of worthwhile secondary offerings. Priester himself underwent a similar transformation after joining the Brewers, completely upending his approach against left-handed-hitters and reallocating his cutter location.

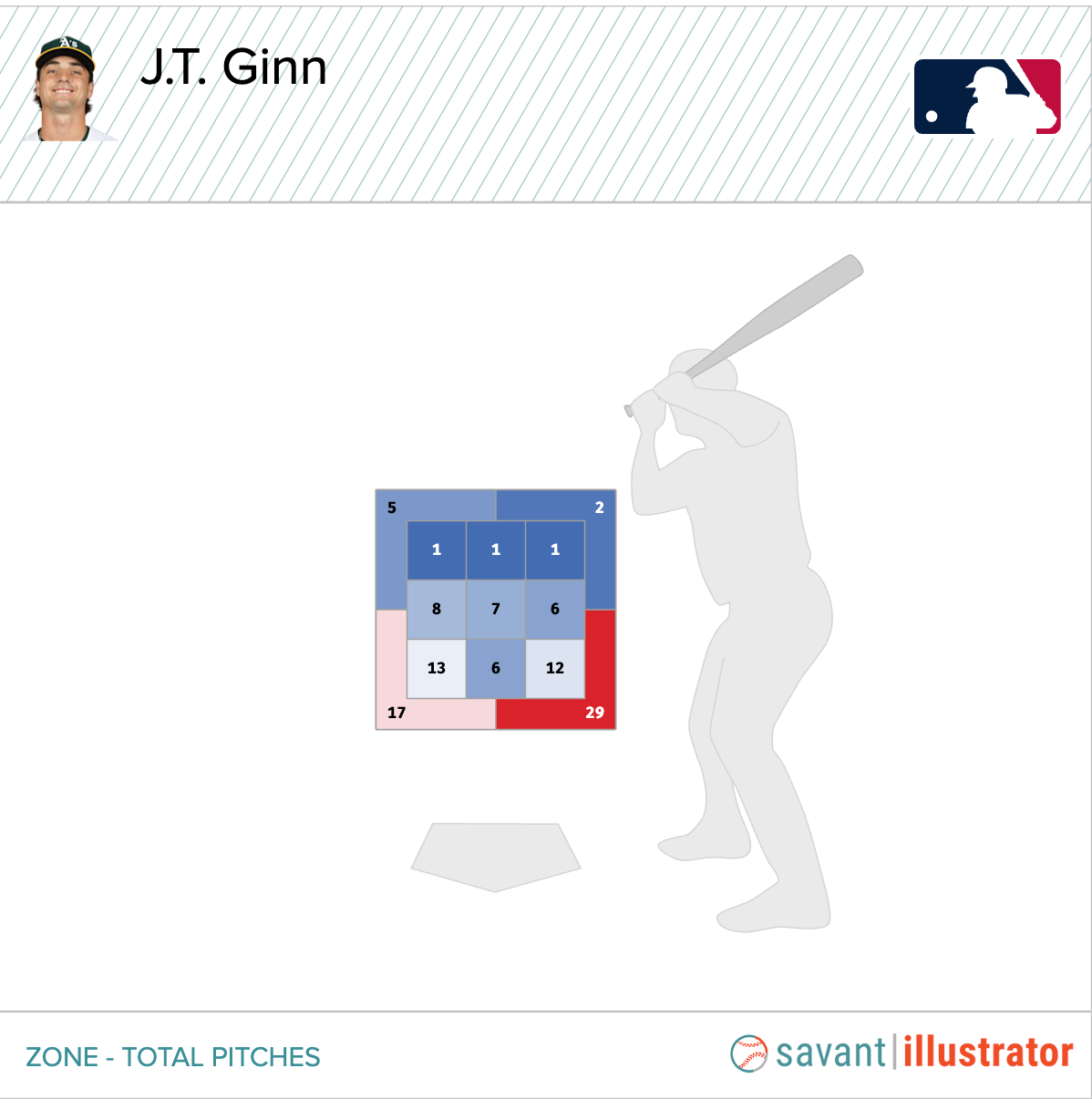

Priester’s cutter sports a 106 location+ compared to Ginn’s 95. Given that Ginn throws his cutter almost exclusively to lefties, let’s compare cutter location between Priester and Ginn:

The difference is immediately apparent. What location+ appears to favor in Quinn Priester’s cutter usage is twofold. First, a strike located in the heart of the zone carries more expected value for the pitcher than an out-of-zone offering with effectively zero strike probability. Second, cutters located up and away are difficult to pull in the air with high exit velocities, limiting the most damaging batted ball outcomes. Unsurprisingly, Priester’s 2.3% pull air% on cutters to lefties was the lowest among all MLB starters (min. 30 BBEs). Ginn’s corresponding 16.2% mark ranked ninth-highest and sat well above the 9.5% league average on cutters to lefties.

I would keep Ginn’s slider as is against right-handed-hitters. Given the goal of preventing pulled fly balls and barrels, the slider already performs well, with accompanying metrics that hover around or exceed league average. Ginn is already an elite pitcher against righties. Last season, he held right-handed-hitters to a .260 wOBA while posting a 31.4% K% – truly elite numbers. Where the cutter and slider burn Ginn is against left-handed-hitters.

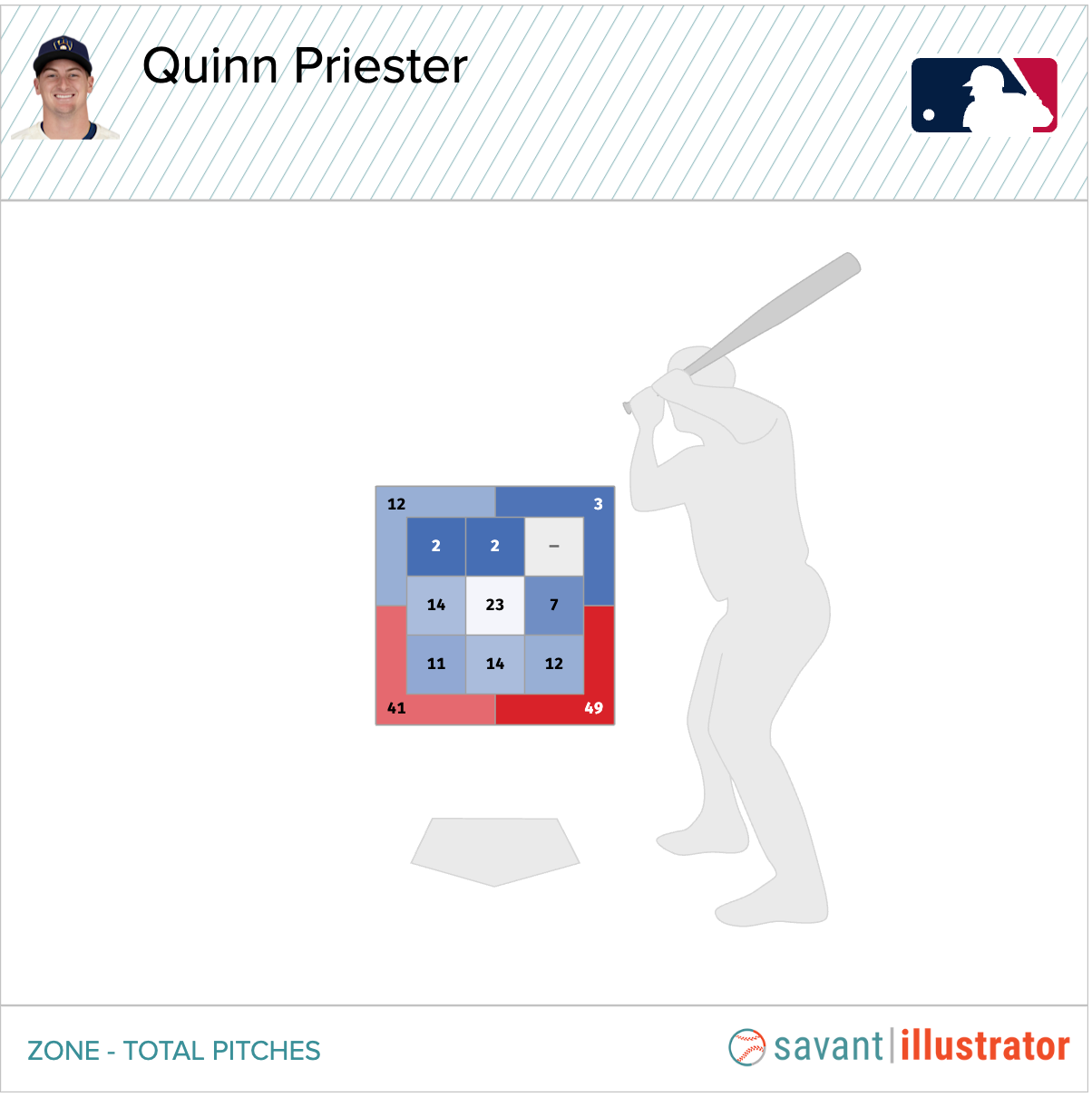

Because of their similar gyro shapes, the cutter and slider need to work hand in hand for Ginn, just as they do for Priester. Noting that both pitchers roughly threw the same percent of sliders to lefties and have similar shapes (both about 86 mph, around 4in of horizontal break, and hugging the zero line vertically), here’s slider location against lefties for both Ginn and Priester in 2025:

On the surface, these plots appear quite similar, aside from Priester showing a more down-and-away tendency. Why does Quinn Priester’s slider post a barrel rate roughly one-third of Ginn’s, an xwOBAcon 80 points lower, and a hard-hit rate eight percentage points lower against left-handed-hitters? Simply put, Priester’s cutter usage allows his slider to play up.

At present, Ginn attacks the outer half of the plate with changeups, cutters, and sinkers. The changeup’s shape bears little resemblance to either the cutter or sinker, and it should likely be scrapped altogether. A cutter located up and away discourages hitters from swinging up in an effort to elevate the sinker, and throwing more sliders down and away achieves the same effect. The shared horizontal movement of the cutter and slider, paired with a roughly six-mile-per-hour velocity difference, introduces meaningful uncertainty for hitters covering the outer edge. If hitters are attempting to elevate outside sinkers, that task becomes increasingly difficult when sliders and cutters consistently live on the black.

The slider-cutter tunnel presents a more natural challenge for left-handed-hitters, in part because it mitigates Ginn’s limited horizontal break on the slider. The cutter allows the slider to play more effectively lower in the zone without requiring a complete overhaul of its shape. In summary, while Ginn is already elite against right-handed-hitters, his pitch location must be adjusted against lefties. The first step is consistently locating cutters up and away to lefties, allowing him to maintain his slider location without increasing its exposure to damage. By simply transforming his cutter location, Ginn should begin inducing weaker contact on sliders to left-handed-hitters.

In addition to these incremental adjustments, Ginn profiles as a natural candidate to add either a curveball or Clay Holmes-esque sweeper. When evaluating pitchers with outlier sinkers like Ginn’s, the first instinct is to lean into an east-west approach. The westward complement to an east-bound sinker has traditionally been a sweeper, as their supination tendencies allow these types of pitchers to efficiently get to the side of the ball. Ginn’s own supination tendencies are evident in his sinker-cutter-slider pairing, as well as a sinker spin efficiency sitting in the mid 70s. Ginn differs from most east-west pitchers due to his 45 degree arm angle, whereas most east-west profiles fall in the 20-35-degree range.

However, one three-quarters-to-high-slot supinator we’ve seen have tremendous success pairing a sweeper with an elite sinker is Clay Holmes. Now a starter, Holmes previously dominated out of the Yankees pen with a seam-shifted sinker, gyro slider, and sweeper. Part of the reason I’m confident Ginn can add a Holmes-style sweeper to his arsenal is that the two share a similar middle-finger-dominant sinker release.

While the two use different sinker grips, both pitchers rely on middle-finger dominance to subtly “kick” the seams in a different direction. That action produces the now-popularized seam-shifted effect, to which each pitcher’s late sinker movement can largely be attributed to. With sweepers, excessive pointer-finger pressure can often introduce too much spin, causing the pitch to lose shape and become more erratic. A clear mechanical throughline can be drawn between Holmes’ sinker release and the success of his sweeper, and the same throughline may plausibly apply to Ginn.

I view this addition as a way to alleviate Ginn’s heavy sinker-slider reliance against right-handed-hitters. More importantly, it would give him an alternative to forcing sinkers in putaway situations like he has been. Clay Holmes didn’t allow a single barrel to a right-handed-hitter on his sweeper last season. As a pitcher who struggles to consistently throw strikes, the sweeper would simply provide Ginn another viable option in any count versus right-handed-hitters. It would be presumptuous to think that Ginn could perfectly replicate Holmes’ sweeper movement with a 117 stuff+, but Ginn is in clear need of an above-average secondary offering, and the sweeper represents a natural solution that aligns with his biomechanical tendencies.

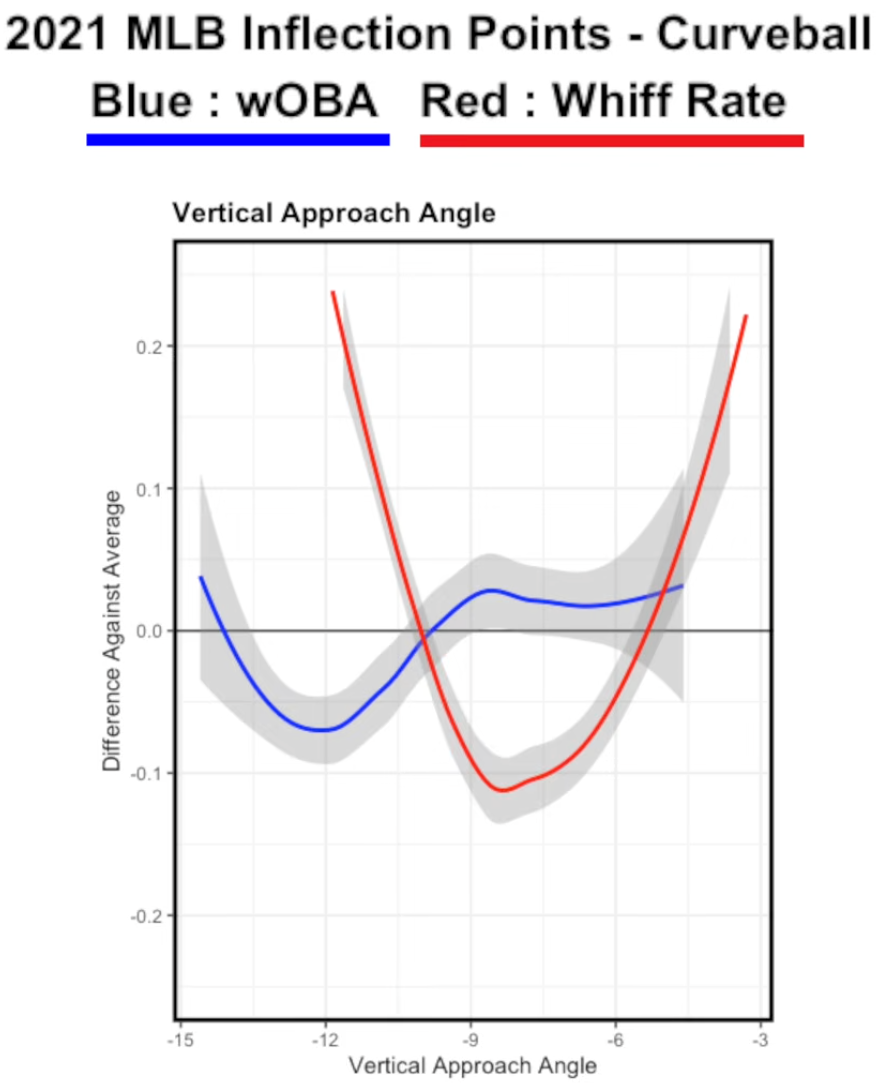

The question of which curveball to add doesn’t have as clear of a solution as the sweeper. My first inclination would be to adopt a curveball akin to Quinn Priester’s. Priester deploys his curveball primarily against left-handed-hitters, with an emphasis on locating it at the bottom of the zone. What stands out about Priester’s shape is how tightly it hugs the zero line horizontally. With that being said, the curveball’s -9 inches of vertical break and minimal vertical separation from his slider leave a lot to be desired, and the pitch’s 103 stuff+, two ticks below the league-average mark for curveballs, supports that belief. We’ve already established that Ginn heavily relies upon his middle finger to manipulate seam effects, and I would aim to leverage that when designing his curveball.

Priester’s grip shows both his pointer and middle finger working in tandem. With Ginn, I would experiment with a spike grip that applies minimal pressure to his pointer finger, allowing the middle finger to drive the pitch. Around 80 mph represents a traditional inflection point where whiff rates spike and wOBA plummets, with any additional uptick in velocity increasing the pitch’s effectiveness exponentially. A spike grip therefore offers Ginn his best path to throwing a curveball in the mid-80s while staying as close to the zero line horizontally as possible.

The primary concern with Ginn's propensity to throw a curveball stems from the vertical approach angles at which he throws his other pitches. The real challenge is throwing from a three-quarters-to-high-slot without the curveball getting overly sweepy. The goal here isn’t to have a plane-changing curveball that plays north-south, but rather a tighter breaking ball that complements the gyro slider.

Image via Tread Athletics

To be effective with this curveball, Ginn will likely need to raise his arm angle a few degrees in an effort to get more on top of the ball, increasing vertical break and achieving a steeper VAA. Last season, Ginn’s non-fastballs were released with a VAA in the mid-7-degree range. The same is true for Quinn Priester. Priester addresses this by throwing his curveball from a 50-degree-arm-angle, compared to a more typical 45-degree slot that he throws his sinker out of. As a result, his curveball VAA (-9.9) is about 2.5 degrees steeper than his sinker’s. Ginn has already demonstrated an ability to vary arm angles with his slider being thrown at a slot roughly five degrees lower than his sinker, but it remains uncertain that he’d be able to make a comparable adjustment in the opposite direction when introducing a new curveball.

Returning to the original question of how Ginn can prevent hard contact, the answer is simply forcing hitters to solve more problems than they currently do. Ginn has been shockingly productive given how one-dimensional his approach has been, and he has his sinker to thank for that. With a sinker of Ginn’s quality, the sky’s the limit, and he may not be far from being a top-30 starting pitcher in MLB. To take that next step, Ginn needs to consistently locate his cutter up and away against left-handed-hitters while experimenting with a sweeper and curveball to add dimensionality to his approach against both sides.